It’s not that I had dreams of breaking out in Chicago’s improv scene. I just really loved the Improvised Shakespeare Company and I wanted brilliant people to have fun with, so I signed up for classes at the city’s hallowed iO theater. When I was 7, I made a conscious decision to become funny after a particularly vicious spate of schoolyard teasing ended with me crying under my desk in the middle of class while my teacher yelled at everyone else. (I still have no idea what “Esther cooties” are supposed to be.) I’d always wanted to be a theater kid, and I was in high school and college, to a certain extent, but I was never able to commit as fully as I craved — it was never something I could devote myself to to the exclusion of academic success.

There was even a time after college when I thought maybe I could be in theater as a career. I’d graduated with a Great Books degree that fills other people’s eyes with boredom, confusion and/or terror when I explain it (I eventually had to shorten it to “a glorified English major,” which hurts my heart in all kinds of ways). I didn’t know what to do with it any more than potential employers did, but I knew I liked my friends and what we did together at University Theater. One abortive summer internship later, I knew I didn’t care enough about the stage to make it my life. I just liked the camaraderie, the teamwork, the collective storytelling, the connection. Improv seemed like a good post-college path to that, which I was sorely missing.

I took classes for, I think, a year and a half. Past a certain point, those who are doing it casually drop out or take a break, and you’re left with the people who really do want to be the next Amy Poehler or (sigh) Chris Farley. I learned so much about storytelling and character-building in those classes, and I made some good friends. Certain things kept me from really giving it my all, despite the extra Saturday morning workshops I attended. The classes were overstuffed and ultimately insufficient; getting 30 people to participate in scenes while giving them the minimum possible feedback left students with one or two chances to try something and learn. I wasn’t interested in constantly partying and going to shows every spare moment I could and interning at the theater and working a shitty job at Groupon, where vast numbers of Chicago’s improvisers wound up. But if this could be my hobby, my clan, I’d be ecstatic to have that.

The time came for a graduation run. Our class chose a name (Who Is Brian Damage?) and a coach, a highly respected improviser and teacher who had also, as it happened, gone to college in my hometown. She was alarmed at how focused we’d all become on getting onto a real team at iO, and spent a lot of time reconnecting us with the joy of improv and of building trust and team connections. Once, we all lay head-to-head in a circle with our eyes closed, humming and singing and listening to each other. When our coach asked how much time we thought had passed, we thought it had been maybe 15 minutes, but it was an hour. It was magical.

Who Is Brian Damage? did shows for two months. We were mostly pretty awful, as beginner Harold teams tend to be. I can tell you that two of my classmates moved to L.A. later and became quite successful, relatively speaking. One friend is doing improv full time, and is working on a cruise ship right now. Some others stayed in Chicago, and some of them stayed in improv, but I’ve largely lost track. One works for the Onion. The point is, I was not asked to join a real team when the time came.

Sure, I was disappointed. There wasn’t much else to do at iO by that point, and I was uncertain about the other theaters in town (Second City just is not funny and I’d never actually seen a show at the Annoyance). But I’d invested hundreds on hundreds of dollars on this stuff, not to mention time and energy, and I wanted to figure out what it was I was missing. So I wrote my coach, who’d had a say in the recommendations, asking if we could meet up for some slightly more detailed feedback.

She said no. You can’t think or argue your way to good improv, she said. You have to let go of thinking and just do it, just feel.

Which struck me as an absolute load of bullshit, and yet I was devastated by her response. All I was asking for was input, pushback, an outside perspective. You very rarely got more than a sentence or two from your teachers, for good performances and bad (though one teacher I really hated told me I could “talk the paint off the walls”). I straight-up didn’t know what I was doing that was worse than the girl who did the horrible baby-talk and made a team somehow.

I never got an answer. It seriously broke my heart for a while. I found myself thinking about it this week after six and a half years. In the journal I kept at the time, I wrote: I am surprisingly upset about this, and I don’t know why. I guess there’s really no good way to say “I feel cut off from a lot of my own emotions, what do I do about that?” Sounds like I was already quite depressed at that point but had not remotely acknowledged it and just thought I was really, really broken.

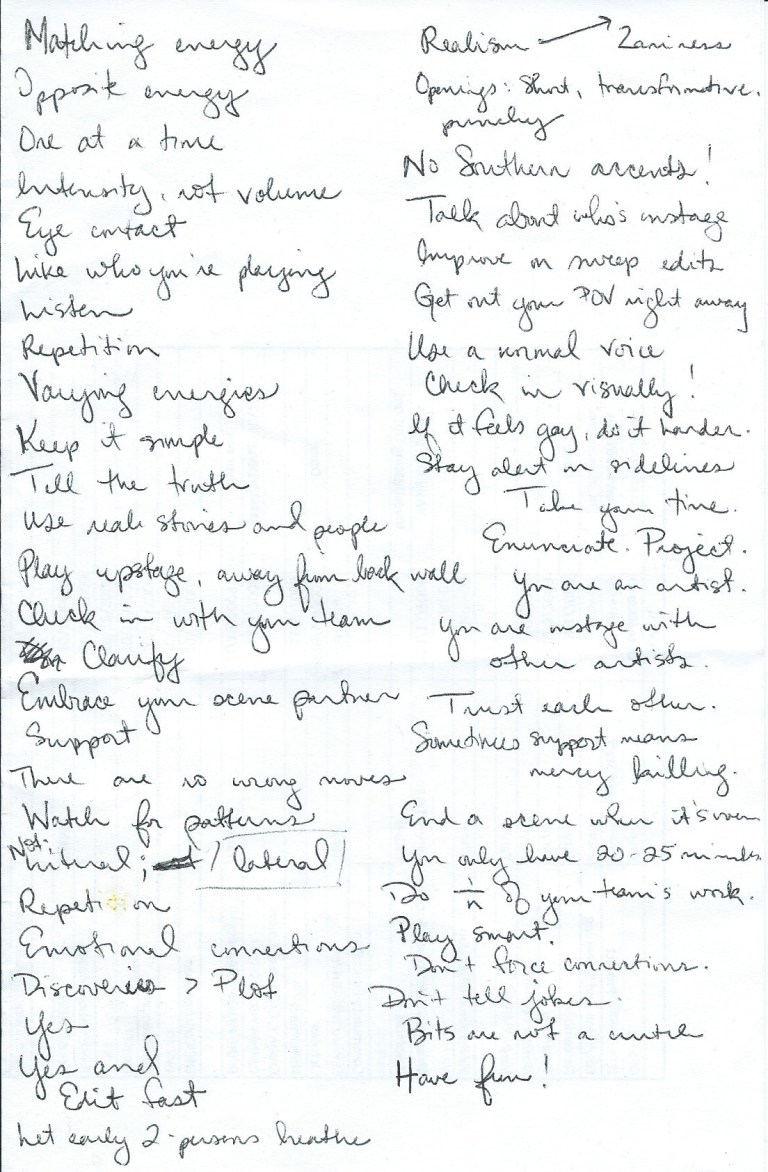

One of the most useful lessons I got from improv was that we connect with emotions and characters much more than we care about plot. I’ve been writing fiction since I was little and have become great at meticulously planning out whole novels, snappy dialogue, moving culminations, clever scenes. By simply choosing a point of view and letting that take you where it will, you definitely can discover amazing stories, whether you’re writing alone or playing with friends (or strangers!) onstage. I used to joke about my writer brain trying to sabotage my barely developed improviser brain, but there’s a lot of fear in trying to control everything about a live scenario, which is something a writer can do. Improv was a huge head-trip, often in really uncomfortable ways.

I took a year of classes at another theater, and it was a joy, in part because the classes were never more than 10 or so people, and so you were given actual information about your play and a safety net where you could make mistakes without feeling like you’d blown your only chance to try something. You could make the point (and many did) that iO wasn’t serving its students or its craft by cramming so many into one teacher’s care. They have a beautiful new theater and training center now, which I hope means this isn’t a problem so much anymore.

Still. I wish I’d known then that I wasn’t broken, I wasn’t insufficient, I wasn’t a castoff. I was scared, I was underserved and I was depressed — I was so depressed. I wish someone had been able to tell me You can and I believe in you, just try again, rather than If you have to ask…

Read more about #52essays17.

<3333

LikeLiked by 1 person